Desert Divide Dozen: PCT Peak Bagging

The San Jacinto Mountains are one of the principal mountain ranges in Southern California. Multiple summits rise more than 10,000'/3050m above sea level. The beautiful but popular northern section of the range offers some of the most best hiking and backpacking in Southern California. But I had something else in mind this past Memorial Day weekend: The Desert Divide, the lesser known and less frequently visited southern section of the range.

The Desert Divid />

The Desert Divid />

The Desert Divide is a major ridge system that stretches south of the main summit region of the San Jacinto Mountains. The Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) ascends this major ridge like a highway on it's journey north. Twelve peaks lie along or very near this section of the PCT–the Desert Divide Dozen. In order from south to north, they are:

- Butterfly Peak (6240'+/1900m+)

- Ken Point (6423'/1958m)

- Lion Peak (6868'/2093m)

- Pine Mountain (7054'/2150m)

- Pyramid Peak (7035'/2144m)

- Palm View Peak (7160'/2182m)

- Cone Peak (6800'+/2073m+)

- Spitler Peak (7440'+/2268m+)

- Apache Peak (7567'+/2306m+)

- Antsell Rock (7679'+/2341m+)

- South (Southwell) Peak (7840'+/2390m+)

- Red Tahquitz (8720'+/2658m+)

Note: Peak elevations shown with a plus sign after the elevation are peaks whose exact height has not been determined by the US Geological Survey (USGS). The height listed is the height of the highest contour shown on the USGS topo map.

On this trip, I and my companions set out to climb these twelve. We knew that it would be a bit of a stretch to fit in all twelve in just 3 1/2 days. None of the peaks are on trail, many have no clear route, several involve class two and class three travel, many are guarded by dense chaparral and, most challenging of all, water would be scarce on the Desert Divide. Water, or lack thereof, would make or break us on this trip. We would travel as light as possible, but unfortunately, there is little one can do to reduce the 2.2 lbs/1 kg per liter that water weighs, and with the warm weather, we'd probably need six or seven liters each–per day. Routes, distances, peaks, and camp sites would have to be carefully coordinated with water sources. Each water source was meticulously researched as to its exact whereabouts and reliability. Since there might be as much as a day and a half's travel to the next water source, any failure to find water at a given source would be serious.

Day One

Our journey starts on the Pines to Palms Highway (SR 74) at the PCT trailhead. Our section of the PCT is just a modest 30.5 miles long, but we estimated that our peak bagging would add another 10 miles to our trek–probably the hardest 10 miles of the trip.

Trailhead sign, Pacific Crest Trail at Hwy 74

To keep the weight down, we started off with only 3 liters each, with a planned refill mid-afternoon.

The start of the trek is easy terrain: Rolling country covered with the dense thicket of dry land brush commonly known as chaparral.

The PCT just north of Hwy 74

Bush whacking through thick chaparral is known to cause travelers thoughts of suicide, but fortunately for us, the PCT provides a well maintained path through the dense vegetation.

The blessed clear path of the PCT through the brush.

Interesting rock formations abound in the first stretch of the PCT, such as this one, the Bishop's Mitre.

The Bishop's Mitre

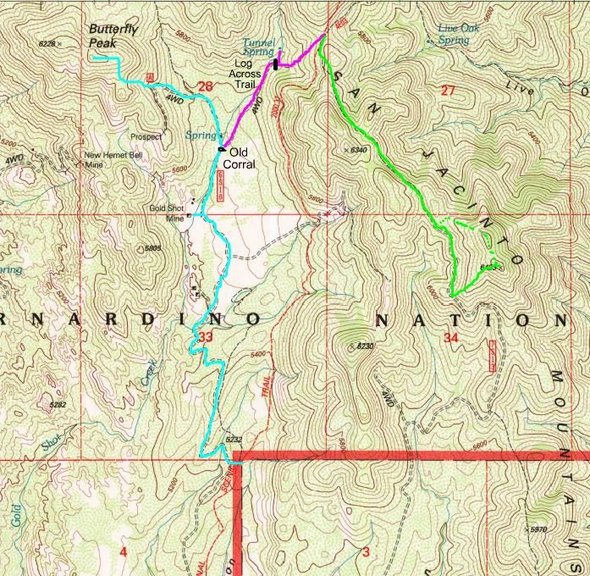

Soon, we took our first detour off the PCT and headed toward Butterfly Peak (6240'+/1900m+). It's not marked on any map, but there's a short connector trail that links the PCT to Forest Road (FR) 6S10. I've marked our route to Butterfly Peak in cyan.

Day One Routes

- Cyan: Route to Butterfly Peak

- Lavendar: Route to Tunnel Spring and return to PCT

- Green: Route to Ken Point

En route, we came across the remains of the Gold Shot Mine.

The Gold Shot Mine

FR 6S10 was clearly a road up to the point where side road leading to the Gold Shot Mine took off. FS 6S10 was still followable after the side road, but it was no longer as clear.

Forest Road 6S10 beyond the Gold Shot Mine

At the junction of FR 6S10 and FR 6S10A, there is a corral built directly astride the road. In order to get to either FR 6S10 or FR 6S10A, one must go through or around the corral.

The Corral astride the junction of FR 6S10 and 6S10A

Our route to Butterfly Peak goes NNW at this juncture and follows FR 6S10A. Calling FR 6S10A a road is somewhat charitable. It may have been a bulldozer track at one point, but it's a road in name only today. The "road" is however signed just beyond the corral. In the photo below, you can see the "road" just beyond the sign.

Forest Road 6S10A sign

The road turns left, crosses a dry creek bed, climbs, and then proceeds to a shallow gully. The route to the peak follows the shallow gully to a ridge top and then follows the ridge up to the summit ridge. We had hoped that an obvious route would have been worn into the brush by the passage of many feet, but no such luck. There was no obvious track and no brush free route.

Looking toward Butterfly Peak from Road 6S10A

Fortunately, the brush wasn't too dense, and we were able to ascend without too much bushwhacking. Soon, we gained the side ridge, then the summit ridge, and then the small summit block (class 2/class 3).

Summit Bloc, Butterfly Peak

From Butterfly Peak, we got our first good views of the next day's first objectives: Lion Pk, Pine Mtn, and Pyramid Pk.

Pyramid Peak, Lion Peak, and Pine Mountain from Butterfly Peak

Not only could we see some of our near objectives, we could see all the way to the highest points in the San Jacinto Mountains:

San Jacinto High Country from Butterfly Peak

From Butterfly Peak, we re-traced our steps back to the corral. It took us some time to find the continuation of FR 6S10. We needed to find FR 6S10 because it would lead us to Tunnel Spring, our first water source. We beat through the brush looking for a road only to realize that the small, single track cow path leading NNE from the corral was the continuation of FR 6S10. That little cow path sure didn't look like a road to us! It was here that we had our first gear failure: The brush was so thick that a water bladder in the outside mesh side pocket of my pack got sliced open as I forced my way through the brush. TIP: Water bladders in outside mesh side pockets aren't such a good idea when bushwhacking. Yes, Nalgene bottles are comparatively heavy (6 oz ea for a one liter hard sided Nalgene), but they may be worth it for bushwhacking.

Heading NNE along the cow path, we crossed a log set across the trail at a right angle. The log marks the short side trail to Tunnel Spring.

The crucial log near Tunnel Spring. Turn north here!

We reached the spring around 2:30 PM. The water was green looking, but we didn't care. We were overjoyed to see it. It was a hot day and we were nearly out of water. Had we not found water here, we might have had to abort the trip or seriously revamp our objectives in order to head to an alternate water source. We tanked up on six liters of water each–thirteen pounds (6 kg) per perons. We knew that we wouldn't see another water source until evening of the following day. After filtration, the water still had a bit of an "oily" taste too it, but it was wet, and we were grateful.

Cattle trough at Tunnel Spring

Heading uphill to re-join the PCT, we followed a heavily eroded bulldozer track.

Follow this bulldozer track from Tunnel Spring to return to the PCT

At the PCT, we turned right (south) and actually headed back toward our entry trailhead for a short distance. Soon though, we turned off on the side trail that leads toward Ken Point. The trail was a bit sketchy in a couple of places, trail maintenance not having occurred in some time.

Brush choked section on the trail leading to Ken Point

The trail joins an old road after two small saddles. From the road, we could see our ascent route, the ridge on the horizon in the below photo that runs up to the summit of Ken Point.

Road leading to the summit ridge of Ken Point

Note: If you look at my route map, above, the solid bright green line marks our route to Ken Point. The dotted line that leads to Ken Point from the north is a route that I read about on the internet but could not find. Our route was brushy but not bad. There had obviously been a fire within the last several years, so the brush wasn't overly tall. My friend Kevin atop Ken Point:

Kevin atop a very windy Ken Point

We did encounter a lot of ticks on Ken Point, but fortunately, we received no bites.

The day drawing on, we beat a hasty retreat down from Ken Point back to the PCT where we resumed our northward journey. The countryside was quite brushy, with not many places to camp, particularly for a group of three. Finally, at about PCT mile 160, we found what we were looking for: An oak grove with a site big enough for three (with room to spare actually). We set up camp and had a lovely meal of garlic pasta shells with sun dried tomatoes and dried turkey.

Campsite, day one

Day Two

On day two, we packed up, intent on hitting five peaks for the day. In terms of numbers of peaks, this would be our most ambitious day, and we'd have fairly heavy packs full of water since we wouldn't see any water all day until evening.

Starting out, we made good time. Too good in a way. We were trucking along thinking that the peak routes would be fairly obvious since these peaks were all much closer to the PCT than the peaks we did the day before. No such luck. We walked right by the route to the first peak, Lion Peak. What a dumb blunder! TIP: A map in your pack is as bad as no map at all. Frequent map checks prevent stupid mistakes.

Speaking of maps, here are the routes for our first three intended peaks of the day:

Day Two Routes

Reaching the route for Pine Mountain, we realized that we had already passed the route for Lion Peak. Crud!

Looking back (!) at Lion Peak

Well, "do what is before you" as they say. Off we went to Pine Mountain. Pine Mountain is a really great peak. There are some brushy parts, but for the most part the route is passable, except for the portion of the route that descends to the saddle just west of Pine Mtn.

Manzanita forest en route to Pine Mountain

There was a lot of up and down on the route to get around brush and rock. The route finding was not always obvious.

The summit of Pine Mountain has a nice little class three section.

Summit bloc, Pine Mountain

The views from the summit are outstanding.

Atop Pine Mountain

After climbing Pine, not to be denied my twelve peaks, I raced back to Lion Peak. Probably a silly thing to do, particularly since the views are not very good from the summit, but I was determined. The retracing cost us at least an hour though.

Summit view, Lion Peak

Next came Pyramid Peak which wasn't bad in terms of brush but was very steep. Here, we're on our way back to the PCT after our ascent. Pine Mountain can be seen in the near distance.

Descending from Pyramid Peak. Note Pine Mountain to the rear.

Unfortunately, we left a water bottle, an entire liter, on the summit by accident. Water being precious, we went back to retrieve it. More time lost.

It's quite some distance to the next two peaks on our agenda, Palm View Peak and Cone Peak. Cone Peak has a nasty reputation for brush and non-trivial route finding.

Approaching Palm View Peak

But as we approached Palm View Peak, we were pleased to finally enter timbered country after having walked the better part of two days in low brush country.

Forested area just south of Palm View Peak

For those not familiar with the Southern California, "mountain" scenery (forests with pines and firs) doesn't really start appearing consistently until one climbs above about 7000'/2100m. Unfortunately, the Mountain Fire broke out in July 2013, about a month after we passed through this area, and all this beautiful timber may now be gone. This is all the more unfortunate because, having made a navigational blunder at Lion Peak and a water blunder at Pyramid Peak, it was now too late in the day for us to make it to Cone Peak and still get all the way to the Fobes Ranch area, our intended camp site and water source. We therefore opted to bypass Cone Peak. We also opted not to do Palm View Peak even though it's easy and very near the trail. Our thought at the time was that we'd need to come by this way again anyway to get to Cone Peak, so let's just do Palm View Peak when we come back.

From the Palm View Peak area, we started down the grade to Fobes Saddle. Fobes Saddle is a real heart breaker because one has to lose over a thousand vertical feet (~300 m) in order to reach the saddle. All of this elevation (and then some) has to be regained the next day. At least the trail is (was) beautiful.

A beautiful section of the PCT south of Fobes Saddle

From the saddle, one must first descend west and then turn NW to reach the small spring just west of Scovel Creek, marked as a blue dot on the below map. There are good spots to camp in the vicinity of the spring.

Route to Scovel Creek and spring

(Click to enlarge)

Note that there are not one but two trails leading west from Fobes Saddle. Make sure you take the right hand branch if you need water. The right hand branch was labeled as the trail to water.

The right hand trail leads to water

The spring is just another cattle trough, but boy were we glad to see it, having not seen water for more than 24 hours. And what luxury to be able to camp near water! I even took a bandana bath. Man! That's living. :)

Cattle trough at Scovel Spring. Danged good water!

Day Three

From the Scovel Creek area, one re-ascends to Fobes Saddle and then begins the climb north out of the saddle.

Climbing north out of Fobes Saddle

We only carried three liters each even though we wouldn't reach any water sources until the following morning. Only three liters for a day on the Desert Divide? Yes, for today we were to be blessed by a trail angel, one Hal S, a volunteer fire lookout at the Tahquitz Peak lookout. I had been talking with Hal before our trip, and he volunteered to carry water up to Apple Saddle and lay in a cache. Thus we were able to make the climb out of the Fobes Ranch area with significantly lighter packs. A special thanks to trail angel Hal!

Beyond Fobes Saddle, one soon enters the Federally designated San Jacinto Wilderness area, one of the premier hiking areas of Southern California.

Entering the San Jacinto Wilderness

As one approaches the 7000'/2100m mark, the trail becomes greener and more woodsy.

PCT just south of Spitler Peak

Hiking along, we came to a real treat on our first peak of the day on Spitler Peak: A well defined use trail leading to the peak!

A well defined use trail leaves the PCT, heading for Spitler Peak

This was so much different than the brushy, trail less peaks we had climbed the two prior days. Here we had a trail and even shade! The author, standing atop Spitler Peak, number eight of the Desert Divide Dozen:

On the summit of Spitler Peak, number 8 of the Desert Divide Dozen

The view of the Garner Valley and Lake Hemet from atop Spitler Peak is outstanding

The Garner Valley and Lake Hemet from atop Spitler Peak

Traveling further north, we soon came to relatively easily climbed Apache Peak.

Apache Peak, as seen from the flanks of Spitler Peak

Here I am, standing on the summit of Apache Peak, number nine of the Desert Divide Dozen.

The summit of Apache Peak

The PCT bypasses Apache Peak some distance to the east. Here, we can see the PCT below us from the upper flanks of Apache Peak:

The PCT from high on Apache Peak

(Click to enlarge)

Rather than retrace our steps to get back to the PCT, we opted to cut cross country down the north ridge of Apache Peak.

Heading cross country from Apache Peak

The terrain and brush were quite doable, and the views down into the desert far below were outstanding.

The desert, as seen from near Apache Peak

As one heads north, the terrain starts to get rough, rocky, and sheer. We were quite grateful to the builders of the PCT. This would be a difficult trip indeed, absent a trail.

The PCT just south of Apple Saddle

Soon, we reached Apple Saddle where we rendezvoused with friends John and Vicki who, happily, were doing the same section of the PCT, sans peaks. John and Vicki would be our ride back to our car the following day.

Rest stop, Apple Saddle

At Apple Saddle, not only did we find John and Vicki, but the precious water cache (three gallons/eleven liters!). Without this water cache, we'd have never made it with such light packs. All five of us give Hal a hearty thanks.

Water cache, Apple Saddle.

Best. Water. Ever.

Heading north from Apple Saddle, we came to Antsell Rock. Antsell Rock is the most challenging and interesting peak on the Desert Divide.

Antsell Rock from its north saddle

Antsell Rock is just that, a rock, and to ascend it, one must do a bit of class three rock climbing. Educate yourself if you're not familiar with what the different classes are. With that climbing comes a certain amount of "exposure," exposure being a climber's term for the potential for a long, unbroken fall. Not only is there rock with exposure, but the approach to the base of the rock requires a good bit of route finding, rock climbing, and bush whacking. It took me a good hour to get to the base of Antsell Rock from the PCT, a distance of only about 1/3 of a mile (about 1/2 of a kilometer)!

En route to Antsell Rock via the north ridge

The route to Antsell Rock involves a bit more detail than is appropriate to go into here. If you're interested in the climb, and I highly recommend it.

After climbing Antsell Rock, I took one last look, and then I moved on up the PCT.

Antsell Rock from the PCT

(Click to enlarge)

I reached the summit of Antsell Rock around 3:30 PM which returned me to the PCT at about 5:00 PM. Darkness would hit around 8:00 PM. The first campable site was still several miles north, I'd be climbing the whole way–and I was still determined to bag Southwell Peak en route. Note: Southwell Peak is named for ranger Jesse Southwell. Most maps merely label the peak "South". Apparently Mr. Southwell was still alive when the map was drawn up, and this didn't sit well with the Board of Geographic Names who shortened the name to avoid commemorating someone still among the living. Despite the official shortening of the peak name, here I use the full name of the peak.

As I ascended the flanks of Southwell Peak, I was treated to fabulous views of Antsell Rock, easily one of the most photogenic peaks in Southern California.

Antsell Rock from the flanks of Southwell Peak

Surprisingly, the PCT which heretofore had been fairly well maintained was a bit brushy. Not bad, mind you, but not what I typically see on the PCT. It was thick enough that it interfered with my trekking poles.

Brushy section of the PCT near South Peak

There was also a sizable boulder down on the trail. Fortunately, it wasn't too hard to bypass on the left (uphill) side.

Large boulder fallen onto the PCT

(Click to enlarge)

Finally, as I ascended the flanks of Southwell peak, I reached the highest point of the PCT on Southwell. Here, there was a fairly clear use trail leading steeply up. Ten minutes later I was standing on the peak in the fading light.

Use trail leading up to Southwell Peak

Some of the route descriptions for Southwell Peak aren't particularly good in my opinion. The approach is from the high point of the PCT on the east side of the peak. If you're traveling south bound, it's just after this rock "wall" (below).

Rock "wall" just north of the jumping off point to Southwell Peak

If you're traveling north bound and you come to the above rock wall, go back perhaps 100 yards/100 meters further, looking for a use trail leading up to the right (west).

I reached Southwell's summit at about 7:00 PM. I only had one hour of daylight left to get to camp! I did not want to be out on this steep and precipitous section of the PCT after dark. Fortunately, I pulled off the trail at a campable site just as darkness fell.

One of the great advantages to hiking in dry country is that there are relatively few insects and it seldom rains. One can "cowboy camp." That is, one can sleep out under the stars without needing a shelter. And so I did.

"Cowboy camping" (sleeping out under the stars) on the PCT. True camping!

I must say "cowboy camping" is my favorite and most comfortable form of camping. Shelters are confining, have problems with condensation, are prone to overheating in warm weather, and block one's view of the night sky. Realistically, shelters buy one little in areas where bugs and precipitation aren't a problem. And camping without a shelter greatly aids in a speedy camp set up and take down.

Day Four

In the morning I arose, tired, but with a sense of accomplishment at having done the hardest peak on the Desert Divide, Antsell Rock. From my camp's vantage point, I took in the view back down the Desert Divide:

Looking back along the Desert Divide

The view of Antsell Rock is particularly good from the eastern flanks of Red Tahquitz, the location of my third night's camp.

Antsell Rock from the vicinity of Red Tahquitz

After taking in the view, I headed east on the PCT through the beautifully wooded Tahquitz Valley.

The lovely, wooded Tahquitz Valley in the San Jacinto Mountains

From the PCT, I had good views of the high country of the San Jacintos. Every peak named in the below photo is over 10,000'/3000m in elevation.

High country peaks of the San Jacintos

The wooded Tahquitz Valley is one of the most beautiful places in Southern California. Note: Much of this area was affected by the July 2013 Mountain Fire. Check for current trail conditions and closures before planning a trip in this area. The PCT in this area is closed as of this writing (early August, 2013).

Looking out over the Tahquitz Valley area

Reaching Little Tahquitz Valley, just east of the PCT trail junction there, I see a most welcome sight: water! This is the first water I've seen since the cache yesterday around lunch time, and this is fresh, flowing water, not water from a cattle trough. Lovely, truly lovely.

Tahquitz Creek–and WATER!!

We leave the PCT here at the Little Tahquitz junction. Oddly, the PCT takes a more roundabout route to get to Saddle Junction, where we'll catch the Devil's Slide Trail to Humber Park, our exit trailhead. Here's a map of our detour (below). Note that our "detour" is actually a more direct route to Saddle Junction.

PCT detour and exit route

(Click to enlarge)

Our detour from the PCT rewards us with a trip through lovely Tahquitz Meadow.

Tahquitz Meadow

Shortly thereafter, we reach Saddle Junction, and we turn off the PCT for the final leg of our journey.

Trail sign, Saddle Junction

The views from the Devil's Slide Trail of massive Lilly Rock (known to climbers simply as "Tahquitz") are fabulous.

Lilly Rock, a Southern California climber's paradise

At long last, we reach the trailhead and bid fond farewell to the San Jacinto Wilderness, tired and dirty, yes, but quite happy. What a great area for backpacking!

Leaving the San Jacinto Wilderness

At the exit trailhead:

At the exit trailhead in Humber Park

Concluding remarks: On the last day, we had planned to climb Red Tahquitz, the twelfth peak of the Desert Divide Dozen. The views to the east and south from Red Tahquitz are simply outstanding. I had previously climbed Red Tahquitz on two occasions, and my friends wanted to get going, so we decided to skip the peak and head for our exit trailhead. So, having already skipped two peaks on day two (Palm View and Cone), I really only summited 9 out of the intended 12 peaks. Fail! Of course the good news is that even on a "failed" trip, you can still have a a great time going through beautiful country. Failure? Perhaps, but what glorious failure. :) Seriously though, a great trip through the backcountry with good friends can scarcely be regarded as a failure. We had a good time.

I thank you for joining me on this trip up the PCT along the Desert Divide of the San Jacinto Mountains of Southern California,

This trip report was written by former Trail Ambassador Jim Barbour (aka Hikin' Jim).